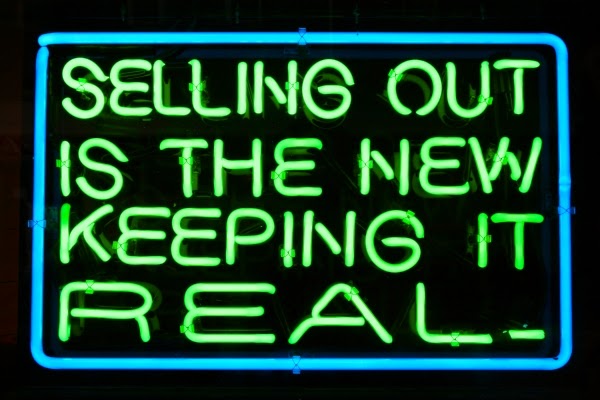

So I ran across

this very amusing piece a few days ago, and it reminded me of a series of posts I wrote to a mailing list back in the days of yore, when mailing lists were the main way people passionate about a given topic exchanged ideas and information—which is to say the prehistoric days around the turn of the century.

I don't recall what started the entire discussion, but it could have been the then-fairly-recent commercial for...an automobile, maybe?...featuring Peter Gabriel's song "Big Time." Or maybe it was Led Zeppelin definitely shilling for a car company. Or Pete Townshend...shilling for a car company. Before he sold perhaps his greatest song to a cheesy cop show. Which was before he sold perhaps his second greatest song to another cheesy cop show.

Whichever it was, it seemed just such a betrayal by one of our greatest artists, something I found shocking and upsetting. Ah, but I was so much older then...

Look. I get it. I do I mean, yeah yeah, it's all very meta, the way Gabriel is saucily taking the piss out of the entire venture by using

that song, of all his songs, to shill a product. So mighty clever. As Pete Townshend, now vying with the Glimmer Twins for the poster boy of what used to be called selling out,

once said:

For about ten years I really resisted any kind of licensing because Roger had got so upset when somebody had used "Pinball Wizard" for a bank thing. And they hadn't used the Who master—and what he was angry about was, he said that I was exploiting the Who's heritage but denying him the right to earn. Who fans will often think, "This is my song, it belongs to me, it reminds me of the first time that I kissed Susie, and you can't sell it."

And the fact is that I can and I will and I have. I don't give a fuck about the first time you kissed Susie. If they've arrived, if they've landed, if they've been received, then the message is there, if there's a message to be received.

I think the other thing is, though—and I'm not trying to sideswipe this, this is not the reason why I license these songs, it's not the reason why I licensed "Bargain" to Nissan—it was an obviously shallow misreading of the song. It was so obvious that I felt anybody who loved the song would dismiss it out of hand. And the only argument that they could have about the whole thing was with me, and as long as I'm not ready to enter the argument, we don't argue. Well, I'm not ready to argue about it. It's my song. I do what the fuck I like with it.

[Emphasis added.]

Isn't that just adorable. "Sure, I took millions but you were all in on the joke, right? If you were a

real fan, you'd have gotten it."

And that sums up Townshend so wonderfully right there, the way he manages to be absolutely right and completely wrong at the same damn time, even as simultaneously compliments and denigrates the hell out of Who fans. As counterpoint,

I present this quote taking the opposite stance:

I had such grand aims and yet such a deep respect for rock tradition and particularly Who tradition, which was then firmly embedded in singles. But I always wanted to do bigger, grander things, and I felt that rock should too, and I always felt sick that rock was looked upon as a kind of second best to other art forms, that there was some dispute as to whether rock was art. Rock is art and a million other things as well—it's an indescribable form of communication and entertainment combined, and it's a two-way thing with very complex but real feedback processes as well. I don't think there's anything to match it.

[Emphasis again added.]

Let's see now, who said that? Oh, that's right:

it was Pete Townshend. Calling his older self full of shit. (To be fair, Pete often calls himself full of shit, not infrequently in the same interview or even breath.)

So. Seems that once upon a time, at least, there was such a thing as the concept of selling out, and that some artists considered this a bad thing. Some of those artists later went on to do the very thing their earlier selves had claimed to find abhorrent. Life's a funny thing, innit?

First of all, let me point out the blindingly obvious, which is that the world has changed since I wrote much of this, 10 long years ago. For the majority of artists—including, yes, major gazillionaires like the Who and the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton and so on and so forth—the only way to get their new stuff heard is by licensing it to a commercial, and that goes quadruple for almost any act younger than U2. So I get that.

The concept of selling out is so old-fashioned that I'm not sure some of today's artists are even aware that it was even a thing, much less thought of negatively. So I may not like that the only way I'll hear a new song by, say, Camera Obscura or Real Estate or The War on Drugs is when they license it for a television show, but I get it. Hey, times have changed, the world moves on, and an artist has to make a living. I oh so very much get that. Trust me, I'm nobody and I've totally sold out more times and more cheaply than I can bear to remember.

But it seems to me that there's a big difference between writing

a song with a commercial in mind (Stevie Wonder's commercial for a local soda of which he was extremely fond) and a song which,

theoretically, was written from the heart (say, "Bargain").

The first is a simple act of craftsmanship and has a long

history, and if that history isn't normally thought of as noble, well, at least some truly

great artists have contributed to it. And when it's simply an exercise, there's

seems to me no great crime against High Art, whatever that may be—it's just providing

a service, and if the end result is of a high enough quality, we're all better

off: there are always going to be commercials, so better good commercials than

bad and, really, is it all that different than Bach writing

The Art of the Fugue as a try-out for a club he wanted to join?

The second one, however, seems to me a betrayal of

everything that truly great rock artists believe in and stand for. I'd have no

moral qualms with Pete Townshend or Peter Gabriel giving up rock to write

commercials; I'd be saddened, maybe, but otherwise, hey. But to write a song from the heart and sell it to the fans with

the implicit promise (and I believe that promise is indeed implicit in

everything those guys said in the first few decades of their careers) that

this

means something to me,

this is what I really feel,

this is a small slice of my soul...and

then sell it to a soulless corporation for a big chunk of change, when neither

of those guys is exactly on their way the poorhouse, seems a despicable act.

Do you really believe that's not the exact pose the Rolling

Stones were attempting (quite successfully) to sell in the 60s and 70s? In

retrospect it's pretty clear that Jagger, at the least, was almost certainly

never some true believer—but they worked hard to embody the total rock and

roll image, which included giving The Man the finger. But if you don't believe

that they tried to make their audience believe that they somehow embodied a

higher version of Integrity than the pop stars of yore, as well as the business

men of the day, you're either kidding yourself or don't know your rock history. 'cuz that's exactly to a T what those middle-class kids posing as rebels were doing.

Now, do I deny that it's their right to do whatever they

want with their work? Of course not. In fact, let's say that again, for those in the back, just to be

perfectly clear: it's their work and they have every right to do whatever they

want with it.

You know what? To make this unmissable, let's say that one more time:

It's their work and they have every right to do whatever they want with it.

But. For them to deny that every fan who gave them their

money and spent hours and hours listening to their work, work that was presented

as one thing, and then to turn around and sell that same piece and allow it to

be used in such an utterly different and contradictory way, is a rejection of

those very ideals that made them attractive to us fans in the first place. It's

a con job. It's saying, here, check out this thing—it's a small slice of my

soul. And you take it as such and perhaps it forms a small part of who you are.

And then ten years later they sell it to an SUV commercial. That's bait and

switch. It's a fine technique for making money. It's impossible to reconcile

with Art or Truth.

Once again, as Townshend himself said: "Rock is art and a million

other things as well: it's an indescribable form of communication and

entertainment combined, and it's a two-way thing with very complex but real

feedback processes."

It's a two-way thing. You give us your music, we give you our money, but in rock and roll that's not where the deal ends. There's, as

Pete Townshend himself said, more—there's feedback and an identification thing that is

perhaps unique to rock and which most of the great bands have acknowledged and

utilized. Townshend himself obviously did (and this is not the only time he

said something along these lines, just the one that was close at hand). Or at least

he did before H+P offered him a couple million.

Look, he and they all have the right to do it. But that

doesn't mean it was the right thing to do. I'll still enjoy their music and

sometimes be touched by it and often marvel at their artistry. But I can no

longer believe that they are the pure artists they would have (or have had) us

believe they are.

And here's the thing: if

artists as diverse as The Doors, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, R.E.M., The Replacements, Sonic Youth, Nirvana and Pearl Jam have all refused to license

their songs (it's extremely notable that McCartney has no qualms about licensing

the songs of others he owns—Buddy Holly, for instance—but refuses to let the

actual Beatles recordings be used) giving up in some cases mind-boggling

amounts of money, then the very notion that there's something distasteful about

the practice isn't absurd. You can disagree with my argument and maybe you're

even right, but these artists obviously agree with me to some extent. And when

someone passes up tens of millions of dollars to avoid doing it, it's something

that needs to be at least given the benefit of some thought rather than

dismissed out of hand.

Now. You'll note that all my examples are of extraordinarily

wealthy rock stars. I don't begrudge Gary US Bonds whatever he made for those

beer commercials in the early to mid 1980s, or Southside Johnny, who did one as

well, or B.B. King for whatever he's done—XM Radio? Sirius? And maybe a hotel

commercial too, right? And diabetes medication. And a fast food chain. And

maybe a few others. God bless you, good sir, say I.

But do you really think at any point in the past twenty-five years that any of

them (toss Etta James in there too) has in their best year made even a third of what,

say, The Stones have made in their worst year? When real life (paying the

mortgage, say) runs up against ideals, real life wins. I mean,

duh. But when you're sitting on a

hundred million in the bank, I kinda feel like staying true to the ideals you espoused

which got your that fortune in the first place just isn't asking too much.

Neil Young clearly feels the same way, given how openly he savaged his friend Eric Clapton in an award-winning video:

As pal DT once said,

Robert Klein once joked, you may recall, that imagine how

set for life Neil Armstrong would have been had he stepped onto the lunar

surface and exclaimed, "Pepsi Cola!" Some moments need to exist for

themselves, and art needs to exist for itself. If it's good enough or, hell,

even mainstream enough, it will take on another life and turn into a

moneymaker. And to that I say, "Groovy."

Two last points and then I'll allow this self-righteous rant to die a merciful and deservéd death. The first is Tom Waits seems to agree with me and, as a general rule of thumb, if Tom Waits agrees with you, you're probably

on the right track:

Songs carry emotional information and some transport us back to a poignant time, place or event in our lives. It’s no wonder a corporation would want to hitch a ride on the spell these songs cast and encourage you to buy soft drinks, underwear or automobiles while you’re in the trance. Artists who take money for ads poison and pervert their songs. It reduces them to the level of a jingle, a word that describes the sound of change in your pocket, which is what your songs become. Remember, when you sell your songs for commercials, you are selling your audience as well.

When I was a kid, if I saw an artist I admired doing a commercial, I’d think, “Too bad, he must really need the money.” But now it’s so pervasive. It’s a virus. Artists are lining up to do ads. The money and exposure are too tantalizing for most artists to decline. Corporations are hoping to hijack a culture’s memories for their product. They want an artist’s audience, credibility, good will and all the energy the songs have gathered as well as given over the years. They suck the life and meaning from the songs and impregnate them with promises of a better life with their product.

Finally, I think Berke Breathed's Bloom County summed it up nicely—and when in doubt, always go with a drawing of a penguin: